January 10, 1501

Some time ago I received a visit from a servant to the Duke Ludovico Sforza. He presented me with a small bag of seven ducats and a letter of request stating that I was to build a working model of a devise designed by master Leonardo da Vinci, the Florentine, and that it was to be ready in four days for a presentation at the ducal court.

Within an hour a servant from Leonardo's workshop arrived with a drawing of a flying wing contraption. With the help of a mirror we read the adjoining text." Is there not more?" I asked. The drawing and text were insufficient I felt. The servant said he would come back with more notes, and I set to work making my own sketches to fully understand the nature and intent of the da Vinci machine.

I first thought my way through the quick sketch of a single arm. I saw a point of pivot and the leading of a rope. The placement of the pulleys meant that the arm, when moved, would straighten or clench like a waving hand.

But while I could see the down-ward pull of the ropes I wasn't sure how the wooden finger would straighten.

When the servant returned with a sheaf of papers I reached for them eagerly. He held them back to his chest! "Three Florins", he said.

"You Imp! " I cried, " what of the Duke's order?"

"Yes", he said, " it would be a shame to fail."

I said I would speak with master Leonardo but he told me the master was away in Florence. I asked his name so I could report him for his scurrilous insolence. He said he was know as "Salai". Yes, I thought, a real "devil"

I realized I had no choice so I paid him a few coins and in an hour and was able to peruse the mirror text. I was able to glean enough of the information I needed and could then dismiss him with a box to the ears for his insolence. I then put myself to the second drawing.

I knew I had enough old wood for the job but went at once to my friend Stefano, the blacksmith, for necessary spring steel and ring bolts, and to my brother Andreo, the sailmaker, for cloth and cordage. By the end of the first day I had amassed all my materials.

Right now had only three days to complete the model. By the Duke's instructions I knew that this model was to be true to Leonardo's drawings but that my job was to reveal only design issues that needed correction, and that I was not to attempt my own innovations.

That was a small relief.

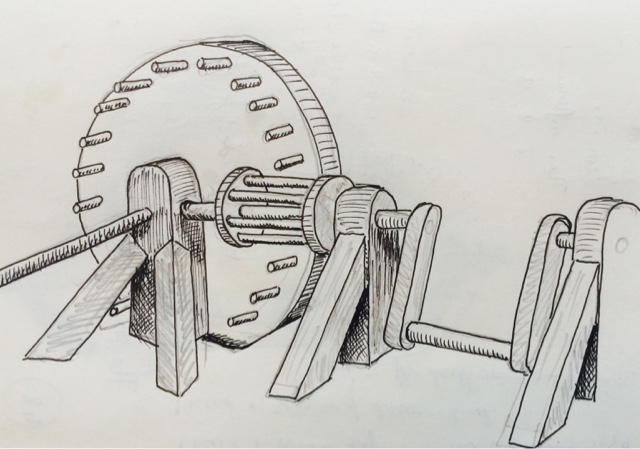

ON THE SECOND DAY my goal was to complete the structure of the "bones" for the working wing. I spent the morning making the central finger and connecting it to the horizontal member which I turned on a lathe. This served as an axle with two extending fingers to help spread the wing. The work with the wood was easy, for that is my trade, but manipulating the spring steel and making the joint work was harder. In the end, however, I was able to get both sufficient spring and flexible stiffness in the joint by using some leather members on either side and, ultimately, stitching a sheath of leather over the whole joint.

With this one component made it was quick and easy to follow up with four other fingers angled into the main axle so they would fan out, and then to add two static rods as a last way of spreading the final fabric.

MY TASK ON THE THIRD DAY was to fashion the bearing arms for the wing, to join the wing to the driving lever with two inter-locked steel rings, and to make the structure through which the driving lever could operate. Again, these tasks were easily accomplished with the help of good augers, and sharp chisels and saws, so as to create the necessary mortises and tenons. My friend Stefano also came through with the last elements required, namely the two inter-locking rings and some good steel spikes.

I mounted this all on a solid base ready for the first trial, and was proud of myself for realizing that the one driving lever would have to be without a point of pivot to ensure that the thrusting aspect of the system would not cause the levers to bind and be locked in place.

In my first fledgling attempt at working the wing I was shocked to realize that the downward thrust, as implied by da Vinci's drawing, was an impossibility.

The sheer weight of the wing structure itself made the wing fall downward. I had to apply considerable force and directional manipulation in order to raise the wing and resist its wish to fall.

At first I was aghast and felt the sweat of fear that I had failed in my job. But then I realized my job was simply to represent the drawings of the great Florentine and, to my best ability, to neither add not take away any element but that which was clearly illustrated (or not). Indeed, with great relief I realized that the Duke's commission was as much to prove that the idea of the wing would fail as that it could be a success. With this thought in mind I went to sleep, with a light heart, knowing that I still had time in hand to complete the fabric wing and to lead the various strings that were part of the flapping mechanism. This would be my task in the final day still to come.